Most of my life I’ve been a fan of strategy games – Risk®, Age of Empires, even Checkers. These games all demand that the player has a solid strategy, or they will likely be defeated by their opponent. Anyone playing without a strategy is just executing random actions based on feeling or intuition (or luck), without a plan, and more often than not, won’t even see their defeat coming. In my experience, the words “strategy” and “tactics” always lead to a great conversation. In one of my previous places of employment, there was so much pressure to be “strategic” that the words strategy and strategic became overused and meaningless – everything was presented as a strategy because that was the perceived path to promotion. Telling someone that their “strategy” was actually tactical execution would lead to heated debates. I have seen people ask for strategy documents and then criticize them for their lack of specifics (which was code for ‘where are the tactics?’).

Strategy

The word “strategy” is derived from the Greek word strategos, meaning the “art of the general.” Simply put, a strategy is a plan to enable you to achieve a desired result. For a military general this is their plan for how they will deploy troops and resources. Conversely, tactics are the specific actions that will be executed to achieve the plan, such as flanking a building in our example.

In a previous post I explains how a Vision sets the overall direction; it is the compass for an organization (or even an individual). With a defined vision you can define the strategies that will enable the vision to become reality. Only once you have defined one or more strategies can you define the tactics that will be used to achieve the strategy (thereby achieving the vision). Take for example a person with high cholesterol who has a vision of being healthy. Their doctor may recommend several strategies for them to bring their cholesterol down and help them achieve their vision of health. One strategy might be to manage weight and/or drive weight loss. Another strategy might be to create a more healthy lifestyle (Note: these are simplified for the purpose of discussion). Each strategy will be achieved by executing a set of tactics, such as engaging in 30-minutes of cardio exercise 3-days a week by running or swimming, or by reducing the amount of animal fat intake, by having vegetarian meals a couple days a week.

Strategy v. Tactics

The difference between strategy and tactics is the difference between a plan and an action. A strategy is the plan–an adaptable plan–for how you will achieve a goal, and the tactics are the executable actions you will perform to achieve the result outlined by the strategy. In military usage, a distinction is made between strategy and tactics. Strategy is the utilization, during both peace and war, of all of a nation’s forces through large-scale, long-range planning and development, to ensure security or victory. Tactics deals with the use and deployment of troops in actual combat (Dictionary.com Unabridged. Based on the Random House Dictionary).

Strategy and Tactics are the plan and the actions.

Creating a Strategy

Creating a strategy, whether for a business, product or person, begins with the Vision; how can you create a plan without a vision of what you want to be when the plan is achieved? Assuming you have a good, concise and specific vision, then defining the strategy or strategies you will use is an exercise in planning. Start by identifying what has to happen in order to make the vision a reality. In the example of the person with high cholesterol who has a vision of being healthy, what has to change is their cholesterol level.

To identify the strategies available you begin identifying concepts that could change the “system” – where the system is the business, product or person. In our example case, the system is the person – what concepts could change this system from its current unhealthy state to a healthy state by lowering their cholesterol? In this case, a lot is known about how to lower cholesterol, so the strategies become apparent quickly:

- Manage weight and/or drive weight loss.

- Improve lifestyle health (e.g. eating, habits, etc.).

- Introduce cholesterol management medication.

With one or more strategies identified you can begin to evaluate them and decide which ones you want to employ. Our example patient may not want to introduce medication at this time, and will commit to the first two strategies. The strategies offer measurement milestones to determine their effectiveness, such as annual physical examination. The measurement milestone is designed to identify if the strategy is working, or if a new strategy is needed.

Measurement is Key

One of the most critical elements to a strategy is the ability to measure its effectiveness. You don’t want to continue burning resources executing against a strategy that isn’t working. With each strategy you identify you must identify a means to measure its success. For example, when we were preparing the initial beta release of Icenium we wanted to attract net-new customers to the company. One of the strategies we developed was to drive awareness through trade press that targeted audience profiles that were different than the current customer profile at the company. We developed a couple of measuring sticks.

When we created the beta release plan we decided that we would allow new users into the system through an invitation code (so we could control the inflow), and to aide the strategy we negotiated an exclusive announcement of the beta (with a couple thousand beta codes to giveaway) with TechCrunch, a publication that targeted the type of user we were interested in. This tactic was designed to support the higher level strategy of driving awareness to new user profiles. Within our system we created a reporting mechanism that would tell us the number of people responding to the invitation who were using email addresses already in our customer database. While not foolproof (because people have multiple email addresses), this did give us a good indication about the number of net-new customers we were bringing into the system, and since they were tied to their invitation code, we could tell where they came from. As we added more press outlets, and gave out more invitation codes, we could tell if our strategy was working or not by evaluating the percentage of net-new users coming from specific trade press.

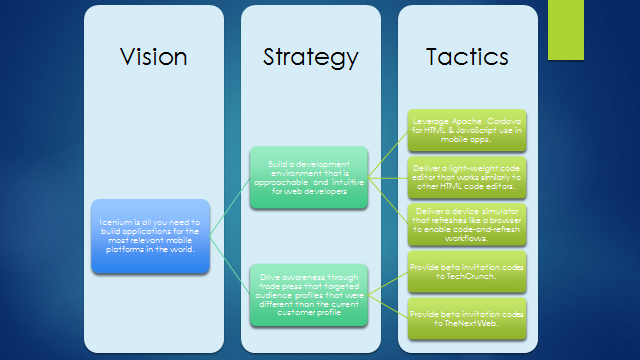

In some cases your measurement may not be as easily instrumented. In another example from Icenium, our vision was to be a one-stop-shop for building cross-platform mobile applications and one of our business objectives was, as I said, to grow the company’s user base. To support both the vision and the business objective, we defined a strategy to attract web developers with an all-in-one tool and service stack. Our strategy was to build a development tool that was approachable and intuitive for web developers. We focused our execution (tactics) on building a light-weight code editor that worked similarly to other code editors, and that eliminated the need to manage platform complexities by abstracting them to the cloud. We replicated the web developer’s normal workflow of code-and-refresh by pairing the code editor with a device simulator. This enabled them to work in the same way they had been working with the browser, but with a focus on mobile applications. We built our app model on open source software that supported technologies they were already familiar with (HTML & JavaScript).

In other words, we defined strategies that would help us achieve the vision, and identified specific actions, or tactics, that would help us execute the strategies. The measurement sticks we created were less analytical and slightly more subjective – a review of support issues, overall community tone about the product, and a survey of users after they had used the product. We even ran a survey of users that abandon the product to find out why they left us (was our strategy failing or were they the wrong user profile?).

Here is a visualization of a couple of these examples:

Strategies Focus on Concepts, Tactics on Specifics

As you may have realized from the examples, a good strategy doesn’t have a lot of specifics about the actions. In fact, a good strategy should be adaptable to start or stop using specific actions, or tactics, at any time. A strategy for managing cholesterol doesn’t specify jogging or swimming, it identifies an amount of cardio recommended to achieve the desired result. If the patient executes the strategy with jogging, and either doesn’t like it, or gets injured, the strategy is flexible enough to allow them to introduce an alternative tactic—swimming—that is still in line with the strategy. Strategies are all about what you can do at a conceptual level – a planning level – to achieve your vision, and the tactics are the specific execution – the specific action – you will take to fulfill the strategy.

Summary

All too often we see people executing with no idea of the over arching strategy. This is when motion is confused with progress. Executing tactics without a strategy to drive them is simply motion. It’s business masturbation. You’re very busy, but nothing useful is going to result from all the effort.

I personally put a huge value in companies and organizations that measure result instead of action; those that value what is accomplished instead of how active people are. You can identify these companies by who is getting rewarded and promoted – is it the people who are thoughtfully developing a plan and executing methodically against it, or is it the people who are very busy with projects that look good, but drive no real measurable advancement toward the vision?

As a Product Management professional I feel strongly that my value is in being able to define a product vision and a set of strategies that will make that vision a reality, and then identifying tactics that I, or others, can execute to fulfill the strategy. More often than not, the execution is done by others, by the troops (engineering, marketing, sales, support). For my product I am the general, and the product strategy is my art.